[Image: "Howl" (2007) by Amy Stein; from The Altered Landscape edited by Ann M. Wolfe]

Nature / wilderness are human inventions. We put them on the fringes of our inhabitation because we've defined them as separate entities. We like the idea of both because through them we believe we understand where we come from and they serve as a datum of where we need to be, how we need to live.

Nature makes us feel good.

Nature is a connection.

Nature is green.

Green equals healthy.

It's hard to argue with these statements because my intuition assigns similar value. But if we were to remove the notion of nature and wilderness from our vocabulary what are we left with? What arguments of sustainability and ecological design can we have? If climate change cannot be defined as a human or natural condition does this alter perception and mode of response? Contemporary understanding of the terms "nature" and "wilderness" might be stated as:

Wilderness is mostly experienced through media.

True wilderness is frightening.

Wilderness provides wildlife habitat.

Wilderness and nature can only be visited by people.

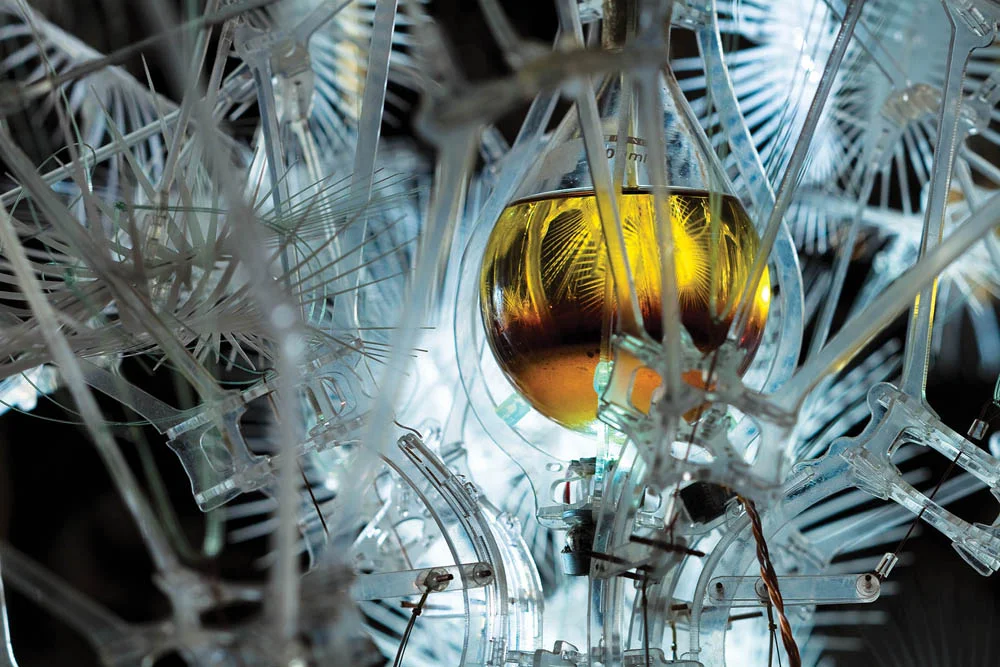

Computers are as natural as a wetland, technology as natural as ecology. Geographer David Harvey writes:

There is nothing inherently unnatural about a built environment such as Manhattan, neither is there anything inherently natural about any landscaped environments. Both the landscape and the urban operate as systems organised around the exchange, processing and distribution of life and matter within contexts which are immanently social, political, and economic, and do so interdependently to form larger ecologies which are not only environmental, but also social, subjective and historically contingent.

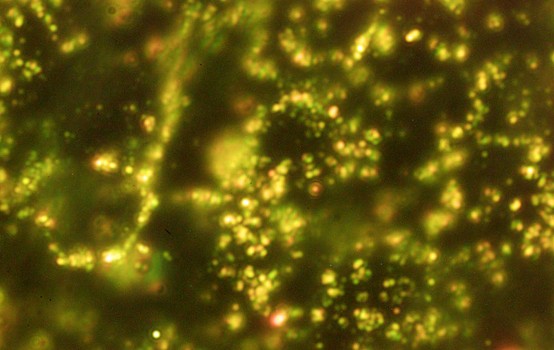

[Image: Gold nanoparticles, courtesy of Georgia Tech]

In nature we identify a healthy organism with growth, but growth cannot exist without waste. But the "non-human" nature has evolved to metabolize all waste, and all byproducts of growth are reintroduced into the system. Cities in this way act very similarly to organisms in relation to growth. If we were to look at a time lapse video of NYC starting 100 yrs. ago this would be very evident, yet we view our waste as a dirty little secret of consumption and production, and not a natural byproduct of a well-functioning healthy city.

Without getting too deep into the origins of man's earthly dominion I ask these questions to challenge the idea of pristine nature in regard to landscape architecture, urbanism, and design responses to reclaimed land, in particularly, landscapes of waste. If we equate waste as growth we can look for a moment at landfill, in particular the well documented developing project of Fresh Kills Park, imagined through Field Operations.

A critique of Fresh Kills by John May in an essay [and another by Mario Ballestros] parallels some of our thinking, in that attempts by landscape architects to return to an idyllic vision of the "bird's in a meadow" depiction has put a stranglehold on what marginal landscapes, or urban parks should/could be. Or even if the use of the term "park" is a appropriate connotation for every public open space condition. Ballestros quoting May writes:

In the urbanism of Fresh Kills, before and after closure, a series of enormous corrective measures and technological “fixes” (along with minor changes in the official rhetoric) are supposed to heal and cleanse and erase the ugly from the site, leaving a landscape that can be consumed without guilt as the “wholly fantastical Photoshop collages of upper-middle class recreational enjoyment” of the proposal demonstrate. One has a nagging sense of this whole idea of a place set back on the right track, and healing itself back to normal is something of a hoax, “a remarkably compelling lie, beautifully rendered, but a lie nonetheless.”

And May again:

There was no acknowledgement of the terrible environmental legacy the landfill had left. Only blind faith in a picture of rescued nature that had been draped both across its unholy terrain and over our collective consciousness.

What interests me about May's writing is a need to challenge the nurturing motherly qualities of so much of contemporary park design. They are safe and green, comforting, depicted through renderings for all walks of life, revitalizing even.

[Hylozoic Ground by Phillip Beesley]

Could we not achieve other positive responses of the human condition through landscapes of fear, danger, and the sublime of the vast? In the same manner that wilderness once evoked these senses, the dark emptiness of the forest, or the scale of the mountain could be designed on Fresh Kills. Imagine massive canyons of bacteria solidified landfill, glowing at dusk through bio-luminescence which responds to toxicity levels within the layers of ground. Heat produced from the breakdown of organic material provides opportunities for microclimates, exotic plantings resilient even in winter disperse the landscape. Cooler moist temperatures mix with warmer pockets creating mist and fog, obscuring the occupants sense of space and time. Upon the massive artificial mountain, the view of the not so distant city becomes clear, but to be able to return is still unsure. Like true wilderness, predatory animals have been re-introduced and all senses must be active to negotiate their presence. There are no soccer fields, and you have never felt more alive.

The metabolizing of waste happens within the landform through bio-tech soil injection [bacteria] and protocell deploying geotextiles which alternate through seen and unseen as they move through the site. Methane capturing architecture is integrated both physically and visually so that the occupant understands the relationship of the living but artificial tectonic transforming under one's feet.

This is an idea of a Neo-Wilderness, taking what we understand of idyllic nature and assimilating that into the margins of urbanisation. These are the zones where growth ends and waste begins to form a spatial condition to experience all that is sublime of the technological capabilities of man and the resiliency of all living organisms.